The Miyamoto Launch Games

The Miyamoto Launch Games

Beginnings

Miyamoto was hired by the President of Nintendo, Hiroshi Yamauichi after his father arranged an interview for him. Nintendo was a toy company and Miyamoto's portfolio was exclusively toy designs. Yamauichi loved the designs and hired Miyamoto as the company's first in-house artist. Expecting to work with toys it came as a bit of a surprise when Miyamoto became tasked with designing art for video games. He designed the hardware for Color TV Racing 112, the character designs for Space Fever (a clone of Space Invaders), and the cabinet art for Sheriff and Space Firebird.

The NES Launch

The early days for Miyamoto at Nintendo were filled with exciting opportunities, but by the NES release in 1985, he was a competent Producer and Designer who had proven himself with hits like Donkey Kong and Mario Bros.

The NES hit NYC in October of 1985 with 17 titles on release. Of those 17 Miyamoto was directly responsible for designing 5 of those games and in one way or another had provided some input on every game available. It is believed that Miyamoto had direct input on the colors available on the NES. How far that reach goes in unknown. While games like Baseball and Tennis had been finished and available in Japan by 1983 and 1984. Super Mario Bros had only released in Japan one-two month(s) before it came to the states.

Interesting to note is that Miyamoto was not responsible for the gimmick games of the NES launch. There are no Zapper or R.O.B games in his gameography and this comes as a surprise given his origin with the toy company.

Baseball - December 7th 1983

Baseball was the first Famicom game that Miyamoto was a designer on. While his Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. games had come out earlier in the same year, those were just ports of his existing arcade games. His console work truly begins here with Baseball as it is released on Famicom before the VS system.

Baseball is incredibly flawed by today's standards. It seems weird that a master designer like Miyamoto would allow a game to restrict the options a player has. Yet here we are with Baseball's biggest flaw, it's lack of fielding. There are 3 particular things about Baseball as a sport that are required: Batting, Pitching, and Fielding. The omission of fielding (or at least control of it) makes this game feel incomplete in many ways. So many games can easily be lost outside of your control by idiotic computer decisions.

Being the first sports game on the system, it was sure to have it's fair share of hiccups, but there is also a lot it gets right. Take yourself back to 1985 and think about what a console experience was supposed to offer. Playing video games was mainly a multiplayer experience and commercials both in America and Japan demonstrated this by always making sure to focus on family fun (Famicom is short for Family Computer) to highlight the value the console had on the living room. Baseball is a great showcase for the multiplayer features of the NES because one player inputs a command (pitching) and the other follows up with a command of their own (batting). It's never so chaotic that both players are inputting at the same times and therefore it's entry to play is incredibly low.

Miyamoto knew Baseball was perfect for consoles. In a developer interview on the Legend of Zelda, he recalls how the in an arcade setting you might have to pay per inning (think like micro-transactions today), but on the NES they could make it so there was a full nine innings and no time limit. It was supposed to be an experience you could enjoy with a family member or friend over the course of an afternoon.

Tennis - January 14th 1984

In many ways, it makes sense that Miyamoto would tackle Tennis as his next NES game. He was familiar with the challenges of developing sports games and having it fresh in his mind probably meant that the ideas came more naturally.

Tennis used to be a basic demonstration for every system. Pong was the first success for video games and its ability to be simple and fun at the same time is what put it on the map. Until more complicated and adventurous games like Super Mario Bros. and Legend of Zelda became the standard for video gaming, the market was mostly seen as a light and fun experience designed for easy pick up and play.

Tennis was necessary for the NES. If Baseball was too simple, Tennis was too complicated. This complication comes from the idea of the Z-axis that unfortunately the NES is only able to barely display. We can't guess why Miyamoto wouldn't focus on a more standard version of Tennis where you simply make contact with the ball and it would return to your opponent’s side of the court, but we can look at the consequences of this decision.

The introduction of the Z-axis takes away the simplicity that Pong offered. The difficulty (ranging from 1-5) shows a severe lack of computer power as the level 1 will frequently just award the player with free points, but the 5 will almost never allow the player to score. However, the biggest setback of Tennis stems from it's multiplayer problem. Baseball nailed the multiplayer by understanding the dynamic of the sport it was trying to emulate. Tennis fails because it only allows a second player to join in a doubles match. The inability to duel in Tennis is definitely an oversight, but it doesn't help that doubles clearly demonstrates the clunkiness of the z-axis even further while also highlighting some new problems.

If Baseball is flawed by its simplicity, Tennis is flawed by it's overcomplexity.

Golf - May 1st 1984

Tasked with yet another Sports game for the system, Nintendo is making something very clear to Miyamoto. They believe in his abilities. Sports games at the time are some of the highest-selling titles on any system. Whether Miyamoto continues to get the Designer assignment after each game or if he wound up developing all three at the same time doesn't matter; the fact remains.

Golf coming as the last of Miyamoto's sports games makes sense. It learns from Baseball's control problems and Tennis complexity problems. We've talked about how golf can be broken down into just seven elements There are five factors in your control and two outside of your control. These seven features make up nearly the entire game and it's kind of beautiful that Golf could be that simple while offering a lot of variety. You control your club, your swing, the force of your swing, and your putt. The game controls the wind and the obstacles (courses). Again, it's simple, but beating your high score is rewarding.

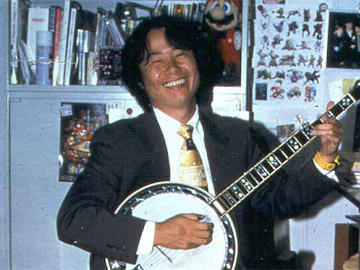

The real question for Golf is whether Miyamoto is getting stronger as a sports game developer (in our opinion he's already proven himself as an arcade developer with Donkey Kong) or if legendary programmer Satoru Iwata is to credit for Golf's success. Truly, what makes Golf hold up are the ease and accessibility of the controls and not the actual gameplay.

Golf continues the focus on multiplayer for console games, but it does so more elegantly than the previous entries. 2-player has two modes, Stroke and Match. It's a welcoming addition to see two types of options for two different types of play. Match ensures that players of different skill don't automatically lose after the first hole or two. Stroke allows equally skilled players to test their strength in a mode where an OB or water hazard could easily spell defeat.

Excitebike - November 30th 1984

To some people, Excitebike could also be considered a sports game by the fact that racing games are somewhat of a subgenre. It would make sense of course that Miyamoto again gets the controller on this one. Excitebike is a great game that still holds up today. It does so because it's a little less grounded in reality than Miyamoto's other sports games. No one today thinks of Miyamoto as a master of realism or a pioneer of sports games. We think of him for the Mushroom Kingdom and Hyrule and the tiny worlds of Pikmin. Miyamoto truly shines when he is allowed to use his vast imagination and develop unique gameplay around that world. Excitebike also differs from every previous Miyamoto game in a big way, it involves a dynamic moving camera. The camera moves with the action, not in a fixed spot like a baseball field or tennis court.

But you won’t find little yellow turtles littered on your motocross track or giant pits that lead to a game over if you're unlucky enough to fall in them. Instead, Excitebike offers a fun and intense racing experience by taking motocross and making it work on the limitations of the hardware. The world and courses are full of personality, gravity is a little lighter, and a hard fall doesn't mean a game over. There are nineteen different obstacles in the game and the combinations and order of those obstacles is seemingly endless. Excitebike is for a more hardcore player that is willing to try and master Miyamoto's system. The interesting thing about Miyamoto's games is that they are mostly easy to understand and more rewarding once you master them. Anyone can complete a course in Excitebike, but the more you play, the better your time will be. There are more mechanics in the game than Donkey Kong could ever produce, but most of them are never necessary to playing the game. That's half the fun of Excitebike, you're able to decide how you want to play it.

More than just deciding how to play this is the first game for the NES that let you decide what you want to play. The inclusion of a design mode is something we loved when playing Excitebike for the first time, but there's a really good reason for that. Multiplayer is impossible in Excitebike due to the limitations of the hardware. It would be impossible to represent two players on one screen traveling at different speeds. Split screen wasn't really a thing yet. Design mode solves that by offering a one of a kind multiplayer experience that was recently rekindled in Super Mario Maker. The ability to make your own tracks and any combination of those tracks allows for endless replayability. If you're still into Excitebike you could still make brand new and challenging levels for the very first time today and attempt to master a new course.

Interlude

At this point Miyamoto has been tasked with four sports games. In Baseball he learned what makes a console experience different than an arcade experience. In Tennis he tried to re-invent a game that had possibly been perfected twelve years earlier. He gives the player control over almost everything but Mother Nature in Golf. And he's figured out his balance between imagination and gameplay in Excitebike. But it's likely these sports games were more of a series of assignments than dream projects for Miyamoto. A game like Mario Bros. was an original idea and concept for Miyamoto. Baseball and the like are more requirements for the hardware.

Ice Climber - January 30th 1985

And so Miyamoto is allowed to shine again in creative fashion with Ice Climber. After pumping out four sports games, it's interesting to see almost nothing resembling sports or the mechanics introduced in those games in Ice Climber. Instead, we see something resembling a hybrid of Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. in a brand-new and original world. Ice Climber feels like a Miyamoto game provided you've played his other notable entries. It expands the platforming of Donkey Kong into a vertical scroll (something we wouldn't notably see again until Super Mario Bros. 2), the rigid and strict jump of Mario Bros., and the item collecting of Popeye. Miyamoto might have made three sports games before this, but you certainly don't feel any resemblance between them.

Maybe that's for the best. Let's think about what a game like Baseball or Tennis could've taught Miyamoto about how to make a platformer. Instead, we are treated to the ice climber Popo and Nana as they trek their way up different mountains increasing in difficulty the longer you play. There's all sorts of Miyamoto weirdness like Polar Bears with sunglasses, collectible eggplants, and jazzy jingles. It feels like Nintendo when you look back on it 30+ years later. Unfortunately, the bad parts of Ice Climber crash down on the game like a slowly building avalanche. It starts with the feeling of the jump, builds with the repetitiveness of the levels, and caps off with the unwelcoming spike in difficulty after a few stages. Difficulty doesn't make a game bad, bad game mechanics make a game bad. I would love to see what Ice Climber could have been if it was released after the game that for the first time in video game history perfected the jump, Super Mario Bros.

Super Mario Bros. - September 13th 1985

The launch titles end with the incredible Super Mario Bros. a title that goes hand in hand with Miyamoto regardless of the topic. It combines everything Miyamoto has learned about the home console experience; jump mechanics, controller simplicity, and also introduces the idea that a challenge can continue to build on itself by quietly adding new mechanics every stage or so. There's so much to be said about Super Mario Bros. that it's not really necessary to talk about it here. Instead I'd like to take a different approach and talk about what Miyamoto's previous NES entries contributed to Mario Bros.

Baseball was Miyamoto's first chance to think about how the home console experience could change video games. Before this, he had only ever designed games that were made to eat quarters. Donkey Kong is fun. But let's be honest, most of us were only ever able to play about five to ten minutes before a game over screen. Baseball doesn't ask you to pay for each inning, but could a full game of Baseball even work in the arcade setting? A leisurely paced 9 inning baseball game across an afternoon is much more feasible in your living room than in an arcade. The same is true for Super Mario Bros. where Miyamoto understood that each stage and world needed to be unique and hold attention for longer than the arcade would be able to offer. I'd argue that if Super Mario Bros. was an arcade game first, we would have just been given World 1 to repeat over and over with increasing difficulty.

Tennis allowed Miyamoto to play around with space and controls in ways much more complex than Baseball. While Super Mario Bros. didn't try to emulate a Z-axis, it's refined controls are a stark comparison to Tennis. The input for the swing of your tennis racket and the jump of Mario boil down to just a single button press, but the difference in feedback is what makes jumping more rewarding. In Tennis, how the ball reacts to the hit of the mechanic depends on many things outside the players control like where the ball is (both on the court and on the Z-axis). In Super Mario Bros, Mario’s jump reacts to your control. How long you’ve been running, how long you hold the jump button, and what direction you’re pushing Mario at that moment. It’s the difference in how much control the player, not the game, has over the outcome.

Golf created an overly simplified way to approach the game of golf. There are five mechanics you control and two mechanics that the course controls. This is a good rule for video games in general, but the idea that Super Mario Bros. refines the things you control to just two things (running and jumping), but allows that input to form a wide array of options is what makes the gameplay satisfying. In golf the ability to select your club depending on power brings the same assortment to its game.

Excitebike offered an energized and exciting atmosphere that enforced level design that was not only well thought out for each courses difficulty, but also dynamic and constantly changing. The Super Mario Bros. series wouldn't get slopes until Super Mario World, but carefully thought out level design including the placement of blocks and enemies is what sets Super Mario Bros. ahead of a game like Kung-Fu* where enemies and objects randomly spawn. It was also suggested by Iwata that Excitebike implement partial screen scrolling that Super Mario Bros. would borrow. Even more interesting, in that same article Miyamoto credits the Warp Zones to Excitebike as well.

Ice Climber is a great precursor for Super Mario Bros. A chance for Miyamoto to explore his creative side with weird and eccentric enemies, while also working on his platforming skills. Ice Climber has a ton of shortcomings, but the most notable is the jump. Countless times in the game you will go for a jump to the next platform and no matter how close you get, unless it's perfect or confidently over the platform, you will fall below and possibly to your death. We can't be certain how Miyamoto developed a jump so differently for Super Mario Bros. and Ice Climber, but let's be glad he did.

And with all of this we have Super Mario Bros. A game that would thankfully sell so well that Miyamoto would understand that this formula is what makes a game successful. Every single one of his games that comes after it is influenced by it, but the launch titles that came before its development also managed to play a role in creating it. The Miyamoto launch games are an interesting assortment. I would have loved to see what direction he might have taken a game like Kung-Fu* or Wrecking Crew.

CONCLUSION

Make no mistake though, Miyamoto definitely didn't do all of this alone. He was guided by Gunpei Yokoi (Producer on all of Miyamoto's arcade efforts), assisted with the programming knowledge of the masterful Satoru Iwata (Golf) and Toshihiko Nakago (Excitebike, Ice Climber, Super Mario Bros), and his wonderful assistant director Takashi Tezuka (Devil World and Super Mario Bros.) The Miyamoto NES launch games offer an interesting look at a man who had somehow pulled off a perfect first try at an arcade game (Donkey Kong) and attempts something entirely different with the console setting. Baseball, Tennis, and Golf all offer gameplay and design thought for your living room than the arcade. It’s clear the intent of these games is to sell the NES into the living room. Baseball and Golf might be nowhere near as much fun as Donkey Kong, but the thought put into the experience and the ability to play them over a period of time easily turns them into system sellers over a game like Donkey Kong.

It’s only after those initial console efforts that Super Mario Bros. smashes onto the scene and does what Pac-Man and Donkey Kong did in the arcades, but in the household. Could Miyamoto have jumped straight from Donkey Kong to Super Mario Bros? This article suggests not. The effort and output of each piece of work continues to build onto the next one. Miyamoto may have been lucky with Donkey kong, but Super Mario Bros. proves that he’s here to stay.

Let’s look at how Tetris has evolved since the classic NES version and see if others have what it takes to stand out.